With elections fast approaching in South Africa, the reporter reflects on 30 momentous years of democracy and how the country has changed since the end of the racist system of apartheid.

My mother told me when she cast her ballot on 27 April 1994 that the vote felt like a “get-out-of-jail card” – she felt empowered.

She was 43 years old at the time – and like millions of other South Africans it was the first time she had voted.

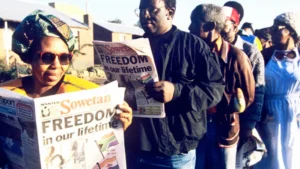

It was the culmination of decades of resistance and armed struggle against racist and violent white-minority rule.

I was too young to vote then, though I was allowed by electoral officials to ink my finger, and I saw what it meant for her and the disenfranchised black majority to be free, to finally choose their own government.

It was tense a few days before the polls with widespread fears of political violence. The whiff of tear gas often filled the air in Kwa-Thema, the township east of Johannesburg where I lived.

Armoured military vehicles drove past our home several times a day and into the night – where gunshots frequently rang out at a distance.

The afternoon before the big day, my friends and I were playing hopscotch in the street when a white truck pulled up full of National Party T-shirts, balls and flags.

This was the party that came to power in 1948 and imposed legal segregation along racial lines, known as apartheid, meaning “apartness”.

Most of us had never owned a new ball before, so we were excited to be given them for free. But our excitement was short-lived.

The “comrades” – anti-apartheid activists – confiscated all of them, the T-shirts were set alight and the balls stabbed with pocket knives.

We were scolded and told: “Never again accept anything from the enemy.” We may have been sad, but we understood why.

The morning of the vote was eerily quiet. It was sunny – yet filled with fear and trepidation.

The polling station was opposite our house – at a teacher’s college. Several blue and white “peace” flags were flying high. Political party agents dressed in their different colours were knocking door-to-door, urging people to vote.

The snaking queues stretched for miles, with young and old lining up raising their fists in the air, chanting “sikhululekile”, which means “we are free” in Zulu.

And I did feel differently – lighter somehow with the realisation that I would not need to look over my shoulder and hide whenever white policemen on horseback passed by.

To this day I may still have a fear of German shepherds, used by the apartheid police as sniffer dogs and sometimes set on us children for no reason during their patrols.

But there are many positive reminders of the liberation struggle in Soweto township’s Orlando West neighbourhood – so much so that a tourism industry has developed there.

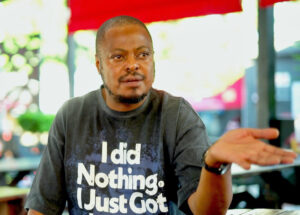

Sakhumzi Maqubela owns a popular restaurant on its famous Vilakazi Street, where both Nelson Mandela, who became president when the African National Congress (ANC) swept to victory in 1994, and Archbishop Desmond Tutu once lived.

“Tourism has benefited Vilakazi Street a lot. I saw tourists walking up and down in awe of what South Africa has become, I then decided to start selling food,” he said.

Mr Maqubela likened his own efforts over the last three decades to those of the country’s leaders.

“The last 30 years have been trial and error for our government, we can give them credit that they’ve been learning.

“I have created 500 jobs here and I sleep better knowing that my efforts have made a difference.”

The early years of democracy were promising: after Mr Mandela’s first term, Thabo Mbeki won the next elections; civil society flourished – as did a vocal and free press.

But many feel the honeymoon is definitely over for the ANC, which is still in power and is mired in allegations of corruption and infighting. The country faces high levels of unemployment, violent crime and many still suffer from a lack of basic services like water and electricity.

The democratic dividends that Mr Maqubela has enjoyed do not spread far beyond the area around Vilakazi St.

Just a 10-minute drive away in Kliptown, rows of portable toilets, that are rarely cleaned or emptied, line the streets.

There are no schools nearby but plenty of shebeens, as bars in residential areas are known here. Young mothers are struggling to get by.

“Thirty years of democracy means nothing to me, there’s nothing to celebrate,” said Tasneema Sylvester, who was sitting outside her shack wearing a sunhat, black jeans and a worn-out red T-shirt.

“I won’t bother voting this year because I don’t see anything that the ANC claims to have done,” said the 38-year-old mother of three.

“I don’t have a job, no clean running water, no toilets. I am angry and hopeless.”

Ms Sylvester’s story reflects a much wider truth in South Africa today – the vast gap between the haves and the have-nots.

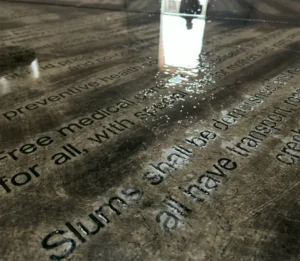

And people in Kliptown feel that their connection to the liberation struggle is often overlooked, given it was here that the 1955 Freedom Charter was signed – the document drafted by those fighting apartheid that set out the vision of a democratic South Africa.

“We’ve been neglected for too long, it’s very sad that none of the 10 clauses of the Freedom Charter have been implemented in this neighbourhood,” said local tourist guide Ntokozo Dube.

For political analyst Tessa Dooms, there are hard questions to consider on the 30th anniversary.

“It’s very clear that people don’t feel like we have fundamentally changed the architecture of our country,” she said.

“There are some glaring things that are still very similar to the past… high levels of inequality persist and have even increased in the democratic era.”

The crisis is illustrated by the hundreds of trained medical doctors who have been staging protests in major cities across the country because they cannot find work.

“It’s very disheartening because the people of South Africa are in dire need of healthcare yet we have a collapsing system and that’s why we have 800 qualified doctors sitting at home,” said Dr Mumtaaz Emeran-Thomas, who is surviving on freelance work unrelated to her medical skills.

Young people especially are demanding change and may abandon any loyalty felt to the ANC for delivering democracy.

There are others who feel so disillusioned that they say they will not vote at all.

Yet the vast majority of people, like my mother, who lived through apartheid, cannot forget the gains and still believe in the power of the ballot box.

And as I will be working on 29 May, the seventh general election under democratic rule, she will be taking my six-year-old daughter with her as she lines up at the same Kwa-Thema polling station where she voted in 1994.