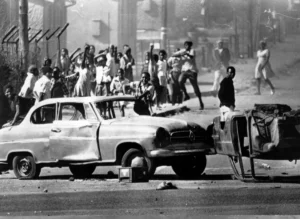

Seth Mazibuko strides into the intersection of Moema and Vilakazi Street in Soweto, gesturing to the spot that changed South African history.

“This is where the students who were marching peacefully had a first confrontation with the police,” he says.

It was June 16, 1976. Mazibuko had turned 16 the day before. Tens of thousands of students, mostly still just children, streamed through the township to protest the racist education system of apartheid.

For decades, apartheid forced many indignities on the non-white population of the country. Perhaps most tragically, it relegated Black South Africans to a sub-par education and reinforced their place in a segregated society.

But few could have predicted the state violence that followed.

The final straw for Mazibuko and other student leaders was the switch to instruction in Afrikaans – a language few of them understood, and the language of the oppressors.

“When we were raising the hands and fingers of peace, we were met with bullets. I still feel guilty today that I led students and children out of the classroom to be killed,” he says.

Hundreds of students were killed, scores of student leaders, like Mazibuko, were sent to prison, and many more went into exile.

The Soweto uprisings, as they have become known, changed the trajectory of the anti-apartheid movement, and set South Africa on the eventual path of liberation.

But as South Africans celebrate 30 years of democracy this week, many educators and activists believe that there is a crisis hollowing out the country’s education system – a crisis that threatens democracy’s hard-fought gains.

“They sold out. Many of the leaders that were supposed to be leading have left this community. They left the people they were fighting for,” says Mazibuko.

Dropping standards

Just up the road from the iconic intersection, Prince Mulwela teaches a geography lesson to senior students at Morris Isaacson High School. It is a misty fall day; most of the lights in the classroom aren’t working.

The school is famous for its instrumental role in the Soweto uprisings, but Mulwela is focused on today’s problems. During his 18 years at the school, he says it has gotten more and more difficult to educate its students.

“It is becoming harder now because the learners we are teaching are so very problematic,” he says, adding that over the past decade children arriving at high school have been increasingly unprepared.

Despite substantial education funding, South African students consistently rank among the lowest in global assessments of literacy and numeracy skills.

Out of the 50 countries of a well-respected assessment of fourth graders, South African students ranked last – more than 80% of 9- to-10-year-olds in the country cannot read for meaning. Longtime Minister of Basic Education Angie Motshekga questioned the usefulness of the international benchmarks, saying that comparing South Africa with wealthy nations like Canada is unfair. However, in at least one study, South African sixth-graders do far worse in math than students in Kenya, a much poorer country. Motshekga says more focus needs to be put on early childhood education and instruction in each learner’s mother tongue, part of a controversial education bill that the government hopes to bring into law. South Africa has eleven official languages. I’m very encouraged. I think from where we started off, I don’t think we could have done better,” says Motshekga, who grew up in Soweto.

A challenging history

To illustrate the country’s challenges, Motshekga refers to her own experience. She says she was the only person from her street to attain a proper education in the 1970s.

Her mother and grandmother were teachers and were able to work around the apartheid system and get her into a Catholic school to finish high school. But the vast majority did not. “That’s why most of my generation are illiterate, unemployed, and poor,” she says.

When Nelson Mandela became president 30 years ago, his ruling African National Congress (ANC) party faced enormous challenges to fix education.

The apartheid education system was a convoluted and racist bureaucracy that had to be undone. There were not enough trained teachers and certainly not enough classrooms.

Now, more than 98% of children aged seven to 14 are in school, according to government statistics. The president recently praised students for their high passing rate in their final school leaving exams known as Matric.

But education experts say that ignores falling standards and high dropout rates.

“In fact, they lie about it when every year we have the festival around the Matric results and they tell us how well they’ve done when it’s not really true,” says Ann Bernstein, the executive director of the Centre of Development and Enterprise, an independent think tank.

Motshekga denied that standards were dropping and said the results show progress.

Bernstein says that South Africa has made meaningful progress in education, but that those gains have slipped in recent years due to corruption, politics, and a lack of political will.

A powerful teachers’ union has also been accused of fostering a “jobs for cash” scheme for teacher placement. Opposition parties and groups like Corruption Watch say that not enough has been done to clean up the education system.

Responding to the most recent accusation relating to jobs, the South African Democratic Teachers Union said last month it “will never condone or tolerate criminal acts in education. The selling of posts is corruption.”

“I think it’s time for the minister to go,” says Bernstein.

For educators like Mulwela, at Morris Isaacson, the problem is obvious. He says education, like many other facets of the state, has been overtaken by a culture of patronage.

“People that are loyal to the ANC, cadres that are loyal to the ANC, are getting jobs in education,” he says. “The government should be saying, ‘let us get people who are qualified for these positions.’”

Earlier this year, the ANC Secretary General admitted that cadre development could be subject to abuse, but said it was key for transformation.

An uncertain future

Many of Mulwela’s students are proud of their school and aware of its role in the protests of 1976.

“They put their lives in danger for a better future, for a better education,” says Mbali Msimanga, a student in her final year.

But she says her generation still faces an uncertain future.

South Africa has the highest unemployment rate in the world and many university graduates struggle to enter the workforce.

“It is scary for us to be sitting at home and doing nothing,” says Msimanga.

“Especially when you went to university for so long and you have a degree, but you are still struggling to get a job,” her classmate, Atlegang Alcock, agrees.

The personal sacrifices of the generations before them were immense.

Mazibuko spent 11 months in solitary confinement at the Fort Prison in Johannesburg, followed by seven years in Robben Island prison off Cape Town – where Mandela, too, served a lengthy term – for calling for a fair education system. He believes that the next generation is not yet “enjoying the fruit of the tree.”

“When we were marching and doing those things, we said that the tree of liberation shall be watered by the blood of the martyrs,” he says. “These kids are not even enjoying the shade of the tree. And for that, I think our country and our leaders are still going to pay dearly.”

In South Africa’s upcoming election, after 30 years of ANC government, that sentiment could be put to the test.